Wannacry is a well-known ransomware, known to have locked away millions of precious photographs and important documents. The ransomware will then request for a certain amount of bitcoin before decrypting your personal files. This post shares about the killswitch mechanism in Wannacry.

This analysis project was a collaboration between Jonathan Cheng and me in Oct - Dec 2020.

Basic Analysis Tools #

When you get the wannacry binary, it’s not going to come in a file named “WANNACRY_MALWARE.EXE”. Wannacry makes use of obscure naming patterns in the Windows registry, blending itself in with a name like 09a46b3e1be080745a6d8d88d6b5bd351b1c7586ae0dc94d0c238ee36421cafa.bin.

So, given an unknown file the first thing to do is to place it in a sandboxed environment like a Virtual Machine, so that the repercussions will not translate to your personal files. Thankfully, there are multiple malware databases like VirusTotal. You can simply upload a file to VirusTotal, and it can compare the entire file hash to known malware hashes, alerting you of any danger.

Now, at this point you might think “Oh, perhaps changing some compile options and strings can change the entire binary’s hash”. Well, VirusTotal is intelligent enough to compare not just the hash, but also certain code sections. It is especially alert to obfuscating code sections commonly used by malware, such as IsDebuggerPresent, which prevents a malware from being debugged easily. If you’re interested in such obfuscation techniques, I’ve created a simple repository of techniques that I previously studied.

Anyhow, it’s not particularly interesting for reverse engineers to look at VirusTotal’s response. Yes we know it’s a malware, but how does it work? We then take a snapshot of it’s key information using PEStudio, ResourceHacker and HashCalc. These tools break down the Portable Executable (PE) format into easily-comprehensible sections and resources that will help us understand how the instruction pointer changes during execution. Again, nothing interesting here but this is basic information used when analysts share information with each other. In reality, there are multiple versions of Wannacry being circulated and we want to pinpoint an exact binary type when discussing its behaviour.

Next, would be analysing its behaviour. It would be ideal if we could map out its entire control flow, but doing that from a binary is extremely difficult, even with the help of IDAPro or Ghidra, which help to disassemble and decompile the binary code to very primitive source code.

Killswitch #

I was surprised when I first learnt about the existence of a killswitch mechanism in Wannacry. This mechanism, when activated, is able to neutralise future instances of Wannacry. And it’s written by the Wannacry authors themselves. I’ll first talk about how the killswitch manifests, and then discuss a little of the question behind all our minds now - why is there a killswitch?

Locating the killswitch in the binary #

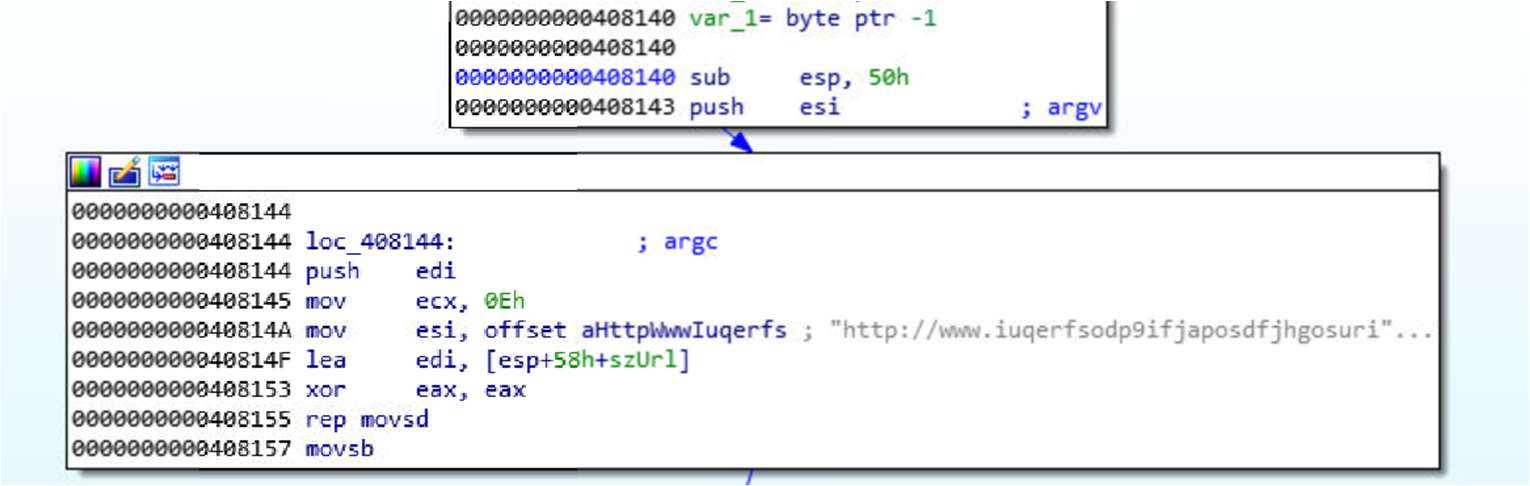

We always check through all the strings in the binary because strings are the most human-readable entities. We found that Wannacry attempts to visit a particular URL.

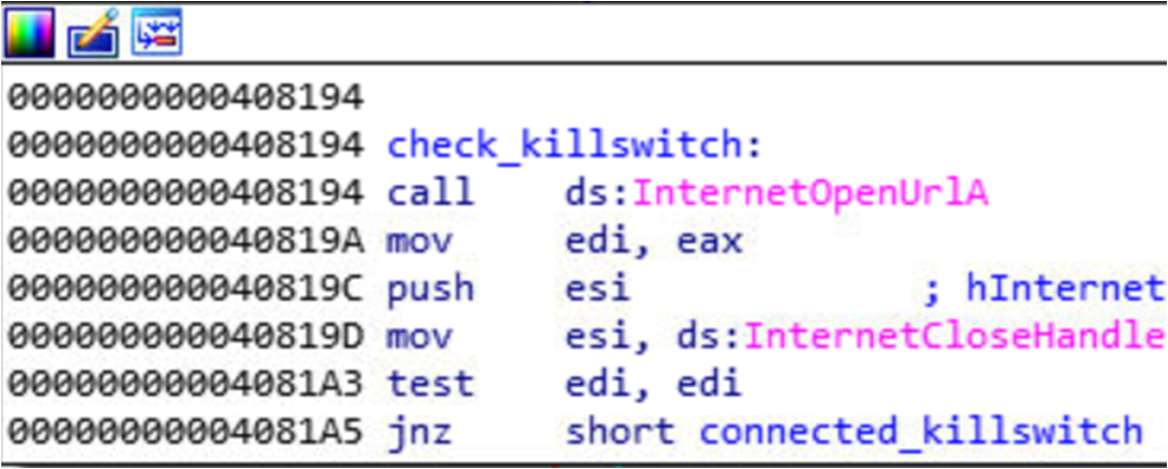

The result of visiting the domain is tested. If the domain is alive and the malware can connect to the site, the return value to InternetOpenUrl (stored in the eax and then edi registers) is 0. Then, the jnz jump is taken.

When the URL can be visited, the malicious payload is not executed. Currently, this URL has been sinkholed by KryptosLogic. This means that any attempt to connect to that domain will be falsely routed to a site put up by KryptosLogic. In effect, it means that the malware trying to access the domain will be successful, preventing millions of malware instances from executing the payload.

In the present state of affairs, many computers have already been infected by Wannacry, saved by the lifeline of being able to reach the killswitch sinkhole.

Thinking ahead, how long can we rely on the goodwill of a company to keep that sinkhole active? Also, it is very simple for the malware authors to simply compile new binaries with different killswitches. How can we effectively manage a new barrage of Wannacry instances?

Why did the authors write a killswitch? #

There are many competing theories behind this, and the reality is probably a combination of many reasons. Seriously, you can dive into a rabbithole reading up about possible reasons for a killswitch, including

- Sandbox evasion. Most user machines would not have been able to visit the non-existent website, whereas virtual machines that emulate a network would pass that check. Then, the malware would not be able to run in VMs. I don’t find this explanation likely because there are multiple more effective VM-detection techniques rather than a killswitch that would nullify all their efforts.

- Used in development, to prevent the worm from spreading to their own machines during the testing process. Also unlikely that someone would forget to release a debugging code for two whole years after the killswitch was discovered.

- Failsafe. The malware could have unintended consequences like crashing the entire host machines instead of merely encrypting the files, giving the hackers no real benefits.

Remarks #

I warmly invite you to dip your hands into taking apart Wannacry, and share anything interesting with me. Our full report is found here.