An amateur programmer would easily find themselves lost in the multitude of programming languages that exist today. In NUS, the introductory programming class is offered in at least four variants (CS1010, CS1010S, CS1010E, CS1010J), each taught in a different programming language. I recall being confused which variant would be “best” for me, and what I would lose out from the other classes. However, as I progressed beyond the introductory module, I started to realise that NUS takes a language-agnostic approach to teaching programming. When assignments are given, we are given the option to complete them in a language of our choice, so long as the final product could be still be fairly assessed.

Sample assignment instructions for a core module (CS2105). Multiple programming languages are permitted, so long as the final output is still correct.

Even when this option to pick any language was not available, we would be expected to pick up a new programming language just for that one module. Over the course of my university journey, I have submitted assignments in more than five programming languages, and often had to learn some of them in a matter of two to three weeks. This language-agnostic approach in the curriculum stands in stark contrast to what employers are looking for – deep knowledge in one or two languages.

Sample job listing for software engineering. Most listings require deep knowledge of one particular language.

This dissonance led me to question the effectiveness of NUS’s language-agnostic approach. How similar are programming languages to each other? What are the benefits and disadvantages a language-agnostic pedagogy? My initial position, like many new to the world of programming, was that all programming languages are founded in logic, and that they would only have syntactic differences. This belief was solidified by the numerous similarities that I encountered in the first few languages I picked up. For instance, translating between Python code and Java code (seemingly) involves pure syntactic translation.

for i in range(10):

print(i)

Program in Python language.

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

System.out.println(i);

}

Program in Java language.

Human Languages #

However, this belief became increasingly unfounded, especially after I had taken a USP class on language (abbreviated as LCC) and started to draw multiple connections between human languages and programming languages.

In LCC, we learnt about one of the biggest unanswered claims in linguistics – whether there exists a language-independent universal thought language shared between humans of all cultures. This claim on a universal “Mentalese” language has a strong parallel to my initial belief of an underlying first-order logic behind all programming languages. One of the elements of a universal language would be universal colour terms. If colour is based on visual perception, then could it be possible that every language would have a similar set of colour terms (e.g. red, blue, black, yellow)?

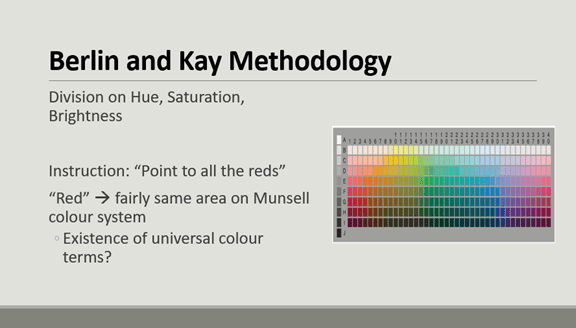

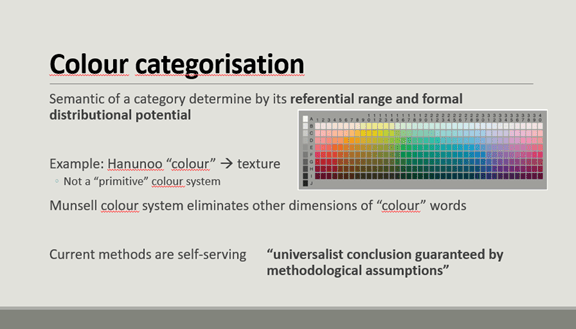

My LCC presentation slide on Berlin and Kay (1969).

Berlin and Kay first set out to prove the existence of universal colour categories across different languages. They would present different cultural groups with the Munsell colour chart (pictured on the slide). Participants would then be asked where “red” in their language referred to on the chart.

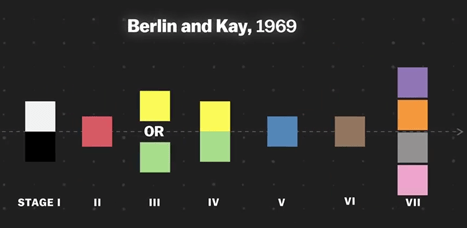

As expected, their research concluded the existence of an evolution of universal colours. Cultures would first have words for red, black and white before gradually adding more colours terms like green and blue to the vocabulary.

Illustration of Berlin and Kay’s findings on the evolution of universal colour terms. Image credit: Youtube.

However, a later research study by Lucy (1997), collected data that revealed how colour words in other languages like Hanunoo do not exclusively refer to hue, as in English. The colour words would also refer to textures like wetness and dryness.

Berlin and Kay did not account for this dimension of colour because they had used a Munsell chart, which only shows changes in hue. This methodology is self-serving in guaranteeing that Berlin and Kay would arrive at the universalist conclusion of colour terms.

My LCC presentation slide on Lucy (1997).

Second (Programming) Language Acquisition #

The idea of self-serving assumptions in linguistic methodology led me to reassess if my assumptions on programming languages were also self-serving. Could programming languages, like human languages, be unique not just in syntactic appearance but also the way that they structure our conceptual thought? In particular, I reflect on my approach to picking up a new programming language (Golang), while coming from a predominantly Python background.

I first started learning Golang by participating in Advent of Code, an online competition where I would have to solve puzzles daily for the 25 days leading up to Christmas. Initially, without any knowledge on Golang, I would think of the solutions in Python, then re-do the question and translate the syntax to Golang.

def count_trees(rule_x, rule_y):

x = 0

y = 0

num_trees = 0

while not is_past_bottom(y):

if is_tree(x, y):

num_trees += 1

x = get_next_x(x, rule_x)

y = get_next_y(y, rule_y)

return num_trees

Solution in Python.

func countTrees(ruleX, ruleY) int {

x := 0

y := 0

count := 0

for !isPastBottom(y) {

if isTree(x, y) {

count++

}

x = getNextX(x, ruleX)

y = getNextY(y, ruleY)

}

return count

}

Solution in Golang. The algorithm in Golang is exactly the same as in Python, just with a different syntax and naming used.

However, as I continued with the motion of pure syntactic translation, I started to get frustrated at how pointless it was to learn Golang. It made me recall one exercise in LCC, where I examined my own bilingual practices and concluded that I would often “speak in Chinese but think in English”. Even though I would express my thoughts in Chinese vocabulary, the sentence structure and grammar are fundamentally English-like. In the same way, I am making this mistake in learning Golang, where I am “writing Golang but thinking in Python”.

All this frustration led to reconsider why I wanted to learn Golang in the first place – definitely not to know more programming syntax. Golang is popular because of its strengths in allowing different pieces code to run concurrently. This is achieved using the goroutine construct in Golang.

Unfortunately, Python had no equivalent of goroutines. This realisation struck me – my methodology of learning Golang by translating from Python would already preclude me from writing goroutines. This was exactly the mistake that the linguists had made with colour words: their methodology of using the Munsell chart to gather data already precluded them from understanding that colour words need not refer exclusively to hue.

Making the connection from human languages to programming languages unveiled the mistakes I had made in learning Golang. In future, I can apply concepts in second-language acquisition to learning Golang. The translation method I used does not let me “interact with existing speakers”, and I can patch this gap by reading and Golang code written by others in the wider community.

Moving Forward: How I Think about Programming Languages #

Many of my friends from non-computing backgrounds who want to learn programming lament that programming is hard to learn, and the language is difficult to understand. However, programming languages are invented by humans and, just like human languages, were invented for communication.

Drawing these varied comparisons between programming languages and human languages made me appreciate how unique each programming language is with its own quirks and bugs. Each new programming language I come across teaches me a new way to understand the nature of programming.

Looking back, I also better understand why NUS would pick a language-agnostic pedagogy. Firstly, broad patterns and concepts and be conveyed without being too hung up on syntactic details. Secondly, and more importantly, such a methodology is future-proof. Human languages are known to descriptively change over the years, as new concepts and vocabulary are invented. In the same manner, programming languages become outdated as new ways to think about structuring code are invented. Each of the 250+ programming language has its own strengths and disadvantages, and it is important to pick the right language for the right task. It is no longer as important to know how to use Python than it is to know when to use it.

A joke that programmers are “multilingual” in a few programming languages.