Kubernetes clusters as an aggregation of resources #

When we are running a small company, we might just run our scripts on a single machine. As our operations scale, we would buy more machines to run them. At this point, we are able to optimise how we run tasks - for example, assigning short tasks to one machine while letting another run a difficult task. Alternatively, we might let one machine rest for maintenance works, and reschedule all its pending tasks to another.

The key idea? Multiple instances of computing power allow us to plan how we run our tasks, while also providing a redundancy buffer. When a system grows large enough to say hundreds of machines, we might group them together to a cluster, which is what a kubernetes cluster aims to do.

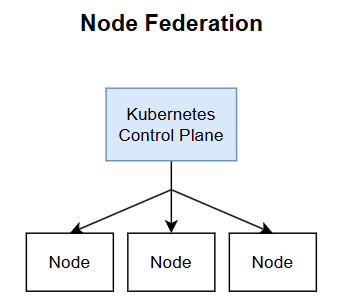

A cluster is simply a group of machine nodes, providing the benefits of combining resources together. We can call this a federation of nodes, with a brain like kube-controller to decide how resources should be allocate within this grouping.

Managing multiple kubernetes clusters #

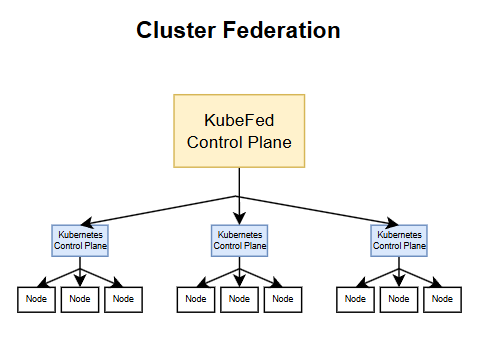

Suppose then, that we want to scale our operations even further, managing multiple kubernetes clusters. Why would we do that? We could run clusters in different data centers, different cloud providers (e.g. one cluster in AKS, one in GKE) or simply as a redundancy in case the cluster brain (control plane) breaks down.

Another common reason for deploying many clusters is due to the limited vertical scalability of kubernetes clusters. As we add more nodes to a cluster, its performance will degrade for a variety of reasons - such as the scheduler simply having to store information on more machines.

As such, we would turn to horziontally scaling kubernetes, by creating more clusters. These clusters can get hard to manage over time, giving rise to the need for multi-cluster orchestration. That is, given a task to run, we would first select the cluster we want to run it in, among many clusters we have.

The selection criteria might include:

- whether it is suitable to run the task in the cluster (e.g. the machine type)

- whether we want to spread resource use evenly between clusters, or

- whether we want to distribute redundant replicas of the same service across multiple clusters.

Key Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) projects targeting this issue include Karmada and KubeFed. This article aims to highlight some issues about multi-cluster orchestration, particularly using the point-of-view of KubeFed.

KubeFed #

A federated k8s control plane is the brain behind co-ordinating how resources are distributed and executed on multiple clusters. This service will be called the “fedbrain” in here, for brevity and also because it does sound catchy.

The fedbrain is responsible for two key tasks.

Resource Scheduling. The fedbrain must decide how resources are distributed to different clusters.

Status Aggregation. The fedbrain must have a mechanism to determine when the resources have been successfully distributed to the various clusters.

Kubernetes-Native API #

Ideally, users do not want to make additional adaptations in order to start using the fedbrain. For instance, I was previously running an identical Deployment on four kubernetes clusters. When I use fedbrain, I just want to send it the Deployment as I would to any cluster. Then, I would expect it to do the multi-cluster distribution on my behalf.

An external user should be agnostic to the fact that a cluster might be a regular cluster or a federated cluster. As such, the federated cluster should work just the same as a regular cluster.

FederatedX #

The federation might have to store some information in the control plane, such as how a resource was distributed previously. This would facilitate future actions like updates or deletions.

The resource might be called FederatedX. For example, we could have ConfigMap and FederatedConfigMap, Deployment and the corresponding FederatedDeployment.

Since kubernetes supports large variety of resources, including self-written custom resource definitions (CRDs), the fedbrain needs to be flexible enough to accomodate both standard and non-standard resources. Standard resources include Deployments, Secrets and ConfigMap. Non-standard resources can literally include anything.

With so many resources, there will be too many FederatedX resource types to define, so we might want to use a standardised and universal FederatedX object that embeds multiple types of resources. This variability can be achieved via the x-kubernetes-preserve-unknown-fields property of CRDs. Doing so also allows for future additions of CRDs without having to support the corresponding logic in the control plane.

Template, Placement, Overrides #

The generic structure of a FederatedX object would include three properties.

Template. Contains the original object that we want to propagate to the various clusters.

Placement. Contains the scheduling result of which clusters the object should be propagated to.

Overrides. With the current structure, we can only propagate the same template object to every cluster. However, we might want to override some fields like the number of replicas, or some cluster-specific labels. Overrides allow us to propagate slightly altered versions of the template.

Cluster Selection #

Suppose we have three clusters available to schedule 10 replicas of an application. How do we decide the ratio of replica division? We can take a leaf from how kubernetes clusters themselves work.

When a kubernetes cluster has hundreds of machines, the kube-scheduler makes decisions of which machines a task should run on. It might consider some machine labels, for instance certain machines might be reserved for premium users. It might also consider the resource available on each machine. Similarly, the fedbrain can extract information on cluster suitability and resource availability to decide which clusters should be selected.

Some services are stateful, and rely on persistent local data stored on a particular machine. In these cases, it is necessary to ensure that the scheduling (1) always selects the same member cluster and (2) always selects the same node within the cluster. Criterion (1) must be fulfilled by the fedbrain, meaning it needs to know when a task requires a static cluster placement. Criterion (2) is already achieved by the native kube-scheduler, through Persistent Volume Claim (PVC) bindings.

Federation Flow #

With these concepts set up, we can construct the flow of information between the external user, fedbrain and the constituent member clusters.

- User sends fedbrain an object.

- Fedbrain “federates” the object, constructing its

FederatedXvariant. - Based on some scheduling rules, fedbrain selects clusters to propagate the object to, and determine the ratio of propagation.

- Fedbrain aggregates the status of the propagation from every cluster, and records and intermediate status in the

FederatedXobject. This status would facilitate any re-scheduling. For instance if one cluster is not responsive we might want to reduce its replicas. - Fedbrain converts the federated status and writes it back to the original object.

- The user perceives that the status of the original object is as desired, and is assured that the propagation has been successful.

Remarks #

Here is a short video that aptly summarises what cluster federation is.

We started with node federation (i.e. a kubernetes cluster). Here, we discuss cluster federation (i.e. a group of clusters). Could we then further extend the concept to a federation of federations?

While multi-cluster orchestration can be beneficial, we have to be certain why we want to even adopt such a complex architecture in the first place. It is important to assess the nature of the use scenario. Simple solutions work the best.