Why do we need balanced scheduling? #

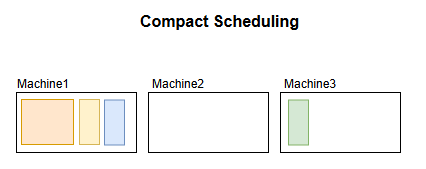

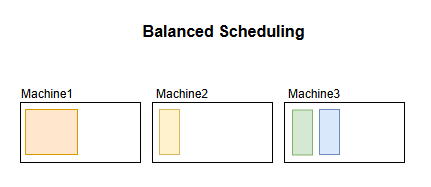

Suppose we have four machines in our kubernetes cluster available to run our tasks. We need to decide between two kinds of scheduling strategies, (a) compact and (b) balanced, which affects the load balancing between the different machines.

A compact strategy would preferentially allocate tasks to the first machine, until it runs out of resources.

A balanced strategy would judge the resource requirements, and fairly disperse it among the different machines.

Both scheduling strategies aim to achieve different types of goals. A compact strategy will improve overall machine utilisation rates, and also allow for improved performance if processes are communicating locally.

On the other hand, a balanced strategy would mean that machines are running with some CPU buffer available, allowing them to better handle burst traffic and I/O requests.

By default, kubernetes comes with its own kube-scheduler, though we can define our own scheduler service to overwrite it. This article explores how we can achieve balanced scheduling using a descheduler.

Resource Specification: Requests vs Limits #

In kubernetes, resources are defined with two parameters - requests and limits. Every resource type will have both a request and limit, and this can be extended from CPU to memory, GPU and even sockets. These request and limit values are defined by the users themselves, and provide the kube-scheduler with an indication of how much resources the task requires.

Limit. This is the maximum amount of resources the service can consume, exceeding which it will be killed. We can think of this as doing a hard limit (prlimit) on the main process of the service.

Request. This is the minimum amount of resources the service must be guaranteed. That is, if a machine has less available resources that what is requested, the service will not be scheduled to that machine. It is a baseline quality of service.

Why not just set request == limit?

#

Oftentimes, many services like web servers are idle unless the service is triggered, so the idle and running usage could differ significantly. When we set a high request value, we have to guarantee machines have resources available, and will quickly run out of machines. This depletion could happen even if many machines are almost idle, since the services are not actively serving users.

Using a Descheduler #

Introducing requests as separate from limits provides the flexibility for burst consumption of resources, yet also brings about a new set of challenges.

Namely, suppose that our cluster of four machines is now mostly idle. It could happen that two services scheduled on the exact same machine #1 both require heavy resources at the same time. For instance, both are trying to perform I/O operations like writing to the disk, or both are competing for network resources.

At this point in time, one machine in the cluster is exceptionally overloaded, while the other three machines continue to remain fairly idle. It is hard to avoid such a scenario entirely, unless we have some knowledge on when each service will have burst traffic. We need to then perform some rebalancing of the services, such as moving one of the burst traffic services to an idle machine.

This can be achieved in kubernetes by evicting the pod of the service. When the pod is evicted, the scheduler will have to again decide where to place this pod. Based on the current machine resource usage (i.e. machine #1 being overworked), the pod will be preferentially scheduled to one of the three idle machines. The net effect is that the machine utilisations are more balanced.

When should we perform eviction? #

Evicting pods causes the whole container creation process to restart, meaning it should be avoided as much as possible. Furthermore, if every machine in the cluster is already overworked, we should not perform any eviction.

An eviction policy might then look like this:

High Water Level. Start eviction if a machine is overworked past a certain high water level.

Significant Difference. Start eviction only if there is a significant difference between two machines’ utilisations. If all machines fall within a utilisation range of say 40% to 65%, we might not want to evict anything as the machine running at 65% is only slightly overworked.

How do we decide what services to evict? #

If there are many services running on a machine, we would preferentially remove these types of services:

- High Usage. Evicting a high-usage service guarantees an instant relief on the machine resources.

- Many Replicas. Even when evicted, the service still remains available for users, reducing the impact of eviction.

However, there are edge cases on eviction that should be reviewed:

- No reliance on machine: Certain machines have specific label selectors for services, or contain local data that the service needs. Even if we evict such services, the scheduler might put them back on the same machine.

- Small and medium services only. Some services use a disproportionately large amounts of resources, say 80% of an entire machine. There is limited value in eviction, because re-scheduling the service merely causes it to solely consume another machine’s resources.

- Ignore socket-only machines. Socket services reserve a set of the machine’s resources. If the machine only supports socket services, then one service’s high usage will not throttle another service on the same machine.

Remarks #

Scheduling and de-scheduling dynamically changing services is a complex affair. The descheduler, while able to achieve balanced scheduling, is not suitable for every scenario and also has the additional downside of restarting services. As usual, we should be discerning in when to adopt such a solution in production.

The descheduler project by kubernetes-sigs can be found here.